The following gives a detailed description of the Akbayan party's platform in the Philippines which advocates participatory democracy. - Editor

(As approved during the 2nd Regular Congress)

Evolution of the Party

Akbayan, being a coalition project of blocs, groups and individuals belonging to different Left and progressive traditions, started and has grown with a strong coalition character. As such, our party carries both the strengths and weaknesses of a coalition undertaking. On the one hand, it provides wider space and latitude for a pluralist exercise and consensus building. On the other hand, it remains relatively loose and slow in responding to challenges, opportunities and threats.

In the course of two electoral battles and a number of mass movement engagements wherein Akbayan had to fight on two fronts—first, with the trapo titans and second, with the extremist and vanguardist parties of the Left, the desire to become a more cohesive party has grown more and more among the members. The 2001 Party Congress, the first regular one, mandated the party to move from a coalition party to a more cohesive one. The party’s National Council interpreted this to mean the development of a unifying narrative—going beyond platform or program unities—and the development of a corps of cadre.

This narrative exercise is meant to unify the party towards a common discourse of the past, the present and the future, a more coherent framework for its electoral platform and mass movement calls and engagements and a shared ethos. This is necessary for Akbayan to develop into a strategic political party, able to merge the various blocs, groups and individual members into a cohesive whole while retaining its pluralist character.

Lenses and Tools for Narrative Building

Our narrative building is a radical departure from all previous ideological construction of the Left. It is both a dialogical and dialectical process between the leadership and the membership, a continuing interaction between party discourse and the discourses of the various communities of our people as well those of the social and political movements throughout the globe.

In viewing the past and charting the present course of our programmatic and party building praxis for radical social transformation, we use the following lenses: class, the community, gender, the environment, nationality and ethnicity and the individuality of the human person.

We consider class as pivotal in light of the deep-seated historical class basis of the economic, social and political exclusion in our country and the widespread and rapid marginalization of the working masses by the contemporary processes of capitalist globalization. Gendered domination permeates in all structures of society and interacts dialectically and dialogically with class. The environmental lens enables us to see class and gender issues in light of ecological limits and the frightening ecological imbalance in today’s world, and how to recreate balanced relations between human societies and Mother Earth. Nationality and ethnicity lenses show us how non-class bonds formed and imagined through decades, even centuries, revealed forms of domination as well as prospects of liberation for the laboring classes as well as women in general. Close to this, the community bonds and traditions unique to Philippine society bring to light the limits and potentials of local politics in transforming national politics and society. And of course, the focus on class, gender, nationality and community must never make us forget the irreducible individuality of the human person.

In this light, we harness the tools provided by structural, institutional, and conjunctural analysis as well as the cultural, feminist, ecological and rights-based critiques to guide our praxis towards a full democratization of power relations and equal access by all to means of producing wealth and knowledge.

Programmatic Vision and Line: Participatory democracy, Participatory socialism

Employing our lenses and tools and harnessing the rich historical and contemporary studies of Philippine and global society as well as the learnings from radical and progressive praxis of social transformation, Akbayan has to develop a clear-cut and distinct vision, program and line for its praxis.

The proposal is: participatory democracy, participatory socialism

This is both a critique and a proposal for construction.

It is a critique of the old statist models, whether of the representative democracy under the capitalist order or the then existing socialism which collapsed. Under both models, the people remain basically deprived of authentic processes of participatory governance. Founded on elitist economic structures, the Philippine brand of representative democracy has none or very little to offer in terms of popular participation in between electoral exercises and a captive of elitist trapo politics and culture during elections. On the other hand, the range of old socialist alternatives focused largely on the state arena, giving little thought to or even disregarding the importance of institutionalizing processes and mechanisms of popular participation and control in th political, economic and cultural spheres. The formerly dominant socialist model even gave rise to a near absolutist state where only one party was allowed to mediate between government and society, even to claim for itself the monopoly of truth, thus resulting in a one party dictatorship. This model also featured a command economy where privilege and corruption became entrenched, strong authoritarian modes of relations within the state, the party and civil society, and an almost exclusively collectivist preference to the detriment of individual rights.

The proposal is an assertion that democracy and socialism can only become a full reality not only by democratizing the state but also by ensuring an autonomous civil society exercising power and constantly engaging the state. It is an assertion for a democratic, horizontal and autonomous character of the relations within civil society. It is also an assertion for individual empowerment within collective undertakings and entities.

We must pursue and complete the struggle for democracy. This includes the consummation of people’s sovereignty and its defense against all forms of imperialism, the completion of land reform, the full inclusion of the marginalized classes and women in the political democracy, and the realization of the right to self-determination of the Moro people, as well as of the indigenous peoples, including the people of the Cordillera and the lumads.

At the same time, it also asserts that the socialist struggle has to be waged both as a critique and an opposition movement to capitalism and imperialism. It has to be waged as a concrete struggle to defend the working classes and people from the daily ravages of capitalist globalization and to win concrete measures to push back the predatory market forces and gain more and more spaces for working people control. Our guiding developmental framework is a mixed economy of market, state and social sectors where an activist state and the social sector engage the markets to develop the productive forces, protects the labor and agrarian sectors, creatively expands the social sectors and fights for fair trade in the global markets.

A party of the working people

The working people are the labor force of the country, the overwhelming majority of the population, most of whom are marginalized, disempowered and poor. They are composed of the various strata of the working class— regular and contractual, formal and informal in industry, service, info-tech and agriculture, and the Filipino labor overseas. They also include the various strata of the peasantry— tenants, leaseholders, seasonal or irregular farmers in small farms and small owner cultivators, the fisherfolk, those of small independent trades and livelihoods and part of the labor force that remains perennially unemployed.

As a whole, the working people are not a distinct class category but embrace a number of classes. As such, the use of the term does not eliminate nor reduce the particularities of the classes in strict terms, their problems and the solutions to these problems. But the description as working people is useful in the sense that it expresses the much expanded scope of the impact of capitalist globalization in the country and therefore, of the marginalization of men and women of labor. A common program to defend their rights, critique capitalism and find measures to empower them in the economic and social and political fields can be devised.

We give special attention to the global diaspora of Philippine labor. Faced by chronic unemployment and meager opportunities for advancement at home and the large-scale opening of the global labor market starting in the seventies, skilled Filipino workers and independent professionals by the hundreds of thousands went abroad to work in contractual jobs or settle down to migrate or become citizens of another state. But the overwhelming majority of these compatriots are still bound to the native soil by ties to their families and national and ethnic identities. In fact, their remittances to their families in the homeland constitute a significant bulk of the national income. Truly, the Filipino nation-state goes beyond Philippine boundaries to include the overseas communities of Filipinos working and living across the globe. Akbayan’s national project includes empowering most of them—still citizens of the Philippines—with a vote so they can have a say in running the affairs of the country, instituting measures—diplomatic and domestic—to protect their labor and human rights in the countries where they work and live, and engaging their active participation in the economic, cultural and social uplift of their homeland.

Akbayan is a party of the working people in the following sense:

First, it draws its membership and base basically from their ranks. Second, it takes their standpoint in the tactical and long-term fights for full democracy, social justice, gender equality and the promotion of socialism. Third, the whole party, from the leadership to the rank and file activists are immersed in their ranks. And fourth, the party ensures the constant development of organic leaders and their promotion to leadership positions from the local to the national.

It is only by developing itself as a party of the working people can Akbayan effectively fight the influence of cynical populism being spread by populist trapos as well as that of the extreme and dogmatic variants of the Left.

The working people character of the party does not mean that it closes the door to compatriots belonging to the upper strata of society whose sense of humanity and patriotism rise above their station in life. We should encourage them to join, especially the younger ones.

Akbayan aspires to become the governing party of the nation. As a party of the working people, it will govern for all, mindful of the legitimate claims of other social interests and guided by the basic principles of democratic and socialist governance.

Feminist

Akbayan is a feminist party. It recognizes that gender inequity permeates in all structures of society. The intersection of male dominance or patriarchy with capitalism, semi-feudalism, ethnic and racial hierarchies, historically creates the complexion of women’s oppression. Thus, Akbayan works to address the unequal power relations between men and women in both the public/productive and private/reproductive spheres of life as it works towards democratic, egalitarian and humanist socialism. Akbayan seeks to empower women and contributes to the struggle of the women’s movement in eliminating all forms of violence against women.

Akbayan seeks to eliminate homophobia as a patriarchal tool to keep both women and men in tight boxes of stereotypical behavior and roles. A human rights violation, homophobia manifests as any act, remark, treatment or attitude that discriminates or abuse another person on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.

The Moro Question and the indigenous peoples

Akbayan recognizes the right to self-determination of the Bangsa Moro people and the indigenous peoples, including the people of the Cordillera and the lumads. Their full political inclusion through a genuine exercise of autonomy and adequate representation in all Philippine state bodies, a just and democratically engaged and negotiated restitution of their claims to their ancestral lands, and full respect for their cultural and religious freedoms are central to reinventing and re-imagining the all Philippine nation and state.

Applying the principle that a party cannot fight for democracy without practicing democracy within, Akbayan establishes the rule that its positions on the Bangsa Moro question and the indigenous peoples question should be the outcome of a discourse and dialogue with the membership of these communities within the party. Akbayan also recognizes the need for autonomous structures for members coming from the Bangsa Moro and the indigenous peoples within the party.

Both a parliamentary and mass movement party

Akbayan draws its basic strength from the organized movements of the working people to work for radical changes and to challenge the traditional political parties with far superior political might, financial clout and organized violence. Alliances with other progressive forces and tactical unities with other parties from time to time can be forged but only to supplement its strength at its base. Akbayan must therefore engage in mass work, mass organizing and mass movements as an electoral party.

But we have to work out constantly and creatively the synergies of our electoral, parliamentary and mass movement work. These are different terrains with different requirements and conduct. We need to develop specific mechanisms for each and define distinct conduct and tactics for the electoral period and for the non-electoral one.

A national party with a global outlook and agenda

Akbayan closely and strongly links itself with the fast-growing global movement to resist capitalist neo-liberal globalization and imperialist wars of aggression, particularly US-Anglo imperialist unilateralism. It considers its national project as an integral part of the global struggle to make possible another world where marginalization by class, gender, race and ethnicity has no legitimate place, a world where humanity is in harmony with the environment.

Akbayan thinks globally but also acts globally as it fosters and nurtures close and strong relations with global social movement networks and organizations as well as any progressive, democratic, socialist, ecological or feminist organization and movement anywhere across the globe to advance the global struggles on all fronts: peace, trade, environment, human rights, debt, gender, defending the South against depredations of the North, and democratizing the United Nations.

Refounding politics, promoting new values

The struggle for participatory democracy and participatory socialism assigns a crucial role to overcoming the deeply entrenched trapo politics of the ruling elite as well as the cynical populism that has grown out of the widespread alienation of the poor masses from the ruling system. Building democracy and establishing social and gender equality require not only overhauling old structures or setting up new ones and establishing new rules but instilling new values and nurturing good old ones as well. Refounding politics in our country will require the promotion and institutionalization of new values like transparency and accountability and nurturing values long accepted but weakly observed and even distorted by trapo politics like respect for citizen’s rights, observance of citizen duties and obligations, citizen action, and community cooperation for the common good.

Akbayan believes that the end result of the new order we seek to establish depends not only on the ends we espouse but on the means we choose in the course of the struggle. While we cannot but recognize that ours is a highly imperfect world and that compromise emerges as a necessity from time to time, ethical parameters must be firmly put in place, always observed and made to guide compromises when these become necessary. We reject the elite trapo’s total lack of scruples and the traditional Left’s strong tendency towards relativity of values, justifying means in terms of ends, all for the sake of the breadth and depth of the class struggles.

Traditional Left parties are held together by ideological monolithic culture and democratic centralist rule. What binds Akbayan apart from its visions and principles is the living practice of its guideposts — humanist, socialist, democratic, pluralist and gender sensitive.

Strategy

Akbayan employs the strategy of combining a determined struggle for ideological and cultural hegemony, establishing building blocks through radical reforms and sustained organizing and constituency building in local communities, sub-classes and sectors and institutions. Akbayan always aims for a critical mass which at a conjunctural moment, when objective and subjective factors are favorably converged, should be guided towards a qualitative leap in the struggle. Such leaps may mean a big electoral victory or even capturing the majority in parliament, a mass upsurge leading to a change in government, or bold radical advances in agrarian reform and other social struggles.

A determined struggle for ideological and cultural hegemony involves a persistent campaign to critique the social and political order and espouse the alternative one, ensuring that such is the framework of tactical battles, developing the internal capacity for discourse and debate, and winning the battle of discourse in the cultural centers of society like the academe, the media, the churches, parliamentary debates and indigenous centers of local discourse.

In the course of the struggle for full democracy, social equality and women’s emancipation, Akbayan aims to establish building blocks of radical reforms. Akbayan employs mass pressure and ideological campaigns while taking seriously the field of engagement with government and/or the private sector to achieve concrete gains for the people and weakening elite rule. This is what distinguishes Akbayan from the traditional Left concept of extreme opposition, always in an offensive oppositional stance, fixated on a unilinear track to total victory, unmindful of partial gains and victories and their beneficial results for consolidating the people’s strength, weakening elite rule and advancing the people’s welfare.

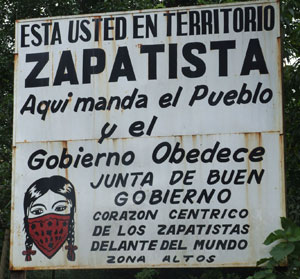

One editor of La Esquina Caliente attended the Venezuela Solidarity Symposium in Washington DC at Howard University last week. Inspired (by community councils and democratic mayors) and outraged (by US intervention), she wanted to post the following article to give our readers a general overview of the information shared at the conference. The event kept a very positive outlook regarding the success of participatory democracy in Venezuela. Each speaker emphasized the great gains that the revolution has made toward giving the people more power to control their economic and social realities but also the fragility of the movement. Much more consolidation and organization will have to happen with Venezuelans who are committed to securing their popular power, but democracy within the PSUV will also have to be considered when examining the processes. While consejos comunales represent an institutionalized relinquishment of state power to the communities, the PSUV has much responsibility in shaping popular participation within the government. The PSUV will play a large role in continuing the revolution when Chavez leaves office and must work to defend the Bolivarian Revolution from imperialist attacks while simultaneously building itself in the most participatory democratic form. For more on this specific topic, please see the Spanish-language article by Gonzalo Gomez who spoke at the recent conference:

One editor of La Esquina Caliente attended the Venezuela Solidarity Symposium in Washington DC at Howard University last week. Inspired (by community councils and democratic mayors) and outraged (by US intervention), she wanted to post the following article to give our readers a general overview of the information shared at the conference. The event kept a very positive outlook regarding the success of participatory democracy in Venezuela. Each speaker emphasized the great gains that the revolution has made toward giving the people more power to control their economic and social realities but also the fragility of the movement. Much more consolidation and organization will have to happen with Venezuelans who are committed to securing their popular power, but democracy within the PSUV will also have to be considered when examining the processes. While consejos comunales represent an institutionalized relinquishment of state power to the communities, the PSUV has much responsibility in shaping popular participation within the government. The PSUV will play a large role in continuing the revolution when Chavez leaves office and must work to defend the Bolivarian Revolution from imperialist attacks while simultaneously building itself in the most participatory democratic form. For more on this specific topic, please see the Spanish-language article by Gonzalo Gomez who spoke at the recent conference: