The following article examines the role of the BBC in promoting citizen participation through their BBC Action Network. An e-democracy promoting website which facilitates grassroots organizing. Evidently some activists have reservations about using a site constructed by a state sponsored institution. The article examines the complexities of a major news organization with links to the state backing such an effort. - Editor

Laurence Pawley - Horizontal politics in a vertical world: The BBC and Action Network

Source: http://www.re-public.gr/en/?p=146

Examining the BBC’s experiments on facilitating participatory e-democracy, Laurence Pawley finds that such re-imaginings of political action must be accompanied by a re-imagination of the institutions that provide them.

The growth of the ‘new’ politics enabled by technological developments like blogs and wikis has, generally speaking, emerged from outside of established nodes of political power. The informal, collaborative methods of action proposed by these spaces have predominantly been taken up by looser social movements and individuals, with the anti-capitalist movement and maverick ‘political bloggers’ serving as obvious examples.

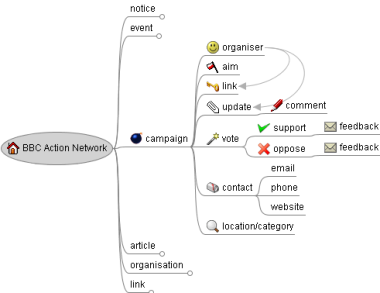

But what happens when similar opportunities are facilitated by a national institution, with substantial links to the state? Can active citizenship be promoted through an organisation associated with a centralised, linear mission to ‘inform, educate and entertain’? This is the question raised by the BBC’s Action Network mini-site (originally launched in 2003 as iCan).  The site takes the form of a facilitative space, aimed in at individuals who wish to develop single-issue campaigns in their local area. Users can leave ‘notices’ (effectively equivalent to a standard online messageboard) or create more permanent ‘campaign’ pages in a collaborative blog format. The site has won several awards for its contribution to e-democracy, and its founder Martin Vogel claimed in late 2005 that Action Network was receiving 175,000 unique users per month.

The site takes the form of a facilitative space, aimed in at individuals who wish to develop single-issue campaigns in their local area. Users can leave ‘notices’ (effectively equivalent to a standard online messageboard) or create more permanent ‘campaign’ pages in a collaborative blog format. The site has won several awards for its contribution to e-democracy, and its founder Martin Vogel claimed in late 2005 that Action Network was receiving 175,000 unique users per month.

In itself, this appears relatively unproblematic. Action Network is a well-organised and relatively simple site, with clear ground-rules that forbid (party) political activity and encourage a collaborative, dialogical dynamic. As such, it shares good practices with other successful examples of online campaign activity, and exudes the ethos of equitable participation central to the ideals behind wiki politics. However, if we begin to institutionally contextualise Action Network within the contemporary BBC, a series of tensions emerge with potential implications for the site, its users, and the BBC itself.

For the latter, Action Network appears to have emerged as part of a concerted effort to integrate notions of participation and public agency into the BBC’s practice. This much was made clear in the Corporation’s 2004 mission statement Building Public Value, which identified Action Network as a key initiative within its new goal of ‘supporting active and informed citizenship’. But how does such a notion function within the BBC? The organisation has long been associated with a centralised and sometimes paternalistic approach to the delivery of public service to a passive public, and has been subject to consistent critique on these grounds. Indeed, one might argue that the BBC is in fact reliant on this position, insofar as only the presumption of a uniform, passive citizenry justifies the continuing prominence of a single public service broadcaster.

Within Building Public Value, this issue is never fully resolved. On the one hand, the BBC (evidently responding to external pressures including media fragmentation, and the development of new discourses of citizenship) is keen to develop a more active, decentred conceptualisation of the public sphere- concluding with the aim to build ‘new civic avenues and town squares… places where we can celebrate, debate and reflect’. Simultaneously however, it lauds the historical success both of the national BBC structure and its successful relationship with Parliament and state institutions, and places considerable emphasis on its ability to set both political and cultural agendas.

In this context, the BBC’s support for initiatives like Action Network implies a contestation of its own position. Put simply, the ideas that underlay Action Network and similar projects (a ‘bottom-up’ approach to citizenship, localism, and the achievement of political goals through non-traditional strategies) exist at least in contradiction – if not in fact in direct opposition - to the precepts that have previously bulwarked the Corporation.

In practice, I would suggest that this contradiction has been largely ignored, with the result that both Action Network and the wider BBC appear somewhat compromised. Although the site maintains a certain level of independence from the BBC, the Corporation maintains the right to place its own postings, provide ‘expert’ advice on campaign methods, and editorialises content (for example, the featured campaigns on the front page). The BBC also clearly views the site’s activity as a potential source of content- in 2006 for example, BBC1’s Breakfast ran a series of reports based on Action Network projects. Even as it encourages open participation, it maintains a strong branded presence.

One argument of course is that such links are beneficial- providing advice and the potential for wider exposure for groups and individuals utilising the site. This however comes at a price, insofar as the BBC ‘preferences’ certain types of action in its advice pages, and certain elements of content in its editorial work. This at least carries the potential to skew the success or failure of certain campaigns, and the types of causes to which the site is deemed amenable. One can argue that any attempt to provide similar forums through a state (or in this case, quasi-state) organisation would carry the same risks, if only because the discursive association between provider and service would seem to privilege particular strands of thought.

In addition, there is a risk that sites like Action Network, because of their particular location, will become as much a complaints forum as a place to ‘celebrate, debate and reflect’. A cursory search for ‘BBC’ on the site leads to campaigns called for the Corporation to be banned, or demanding changes in programming. While such entries don’t necessarily undermine the site’s broader potential, their frequency is illustrative of the difficulties it faces in ‘shaking off’ the legacy of its provider (a fact undoubtedly known to Tony Blair’s government after the recent e-petition on road pricing). If such sites become increasingly ‘hijacked’ as a means to attack their founders, it is possible that other users will seek alternative platforms without such strong associations.

So, there appear to be some definite obstacles in the development of online political networks through an established national body. And should it attempt to resolve them, the BBC – by virtue of the more centralised aspect of its institutional logic – may find itself in an awkward situation. It could for example step back from Action Network, removing the obvious links with BBC content and leaving the site truly ‘open’ to participation. Yet while this might alleviate the concerns of some users, it is unlikely to benefit the BBC itself. If such a move succeeded, it would give ammunition to those who wish to see a more general scaling back of the BBC’s role in UK life. And if it failed (for example because users appreciated the guidance offered by the BBC content), then the Corporation has both failed in its attempt to support active citizenship, and wasted licence-payers money in doing so. Meanwhile, to continue with the current format exposes the BBC to the charge of interference with an ostensibly public-led platform.

This article, it should be stressed, is not intended as a condemnation of Action Network, or of the BBC’s intentions in its establishment. The site has much to commend it, and a glance around it will quickly prove that much useful work is being done, both via the campaigns themselves and the broader encouragement of civic responsibility. Nonetheless, it is perhaps the case that to be optimally effective, such re-imaginings of political action must be accompanied by a re-imagination of the institutions that provide them. Such a solution, while optimistic, offers the best chance of transcending tensions between participation and passivity, centralisation and subsidiarity, and past and future.

Further links:

Action network wins e-democracy award

The BBC plans for digital democracy

BBC Action Network

PARTICIPATORY DEMOCRACY vs REPRESENTATIVE DEMOCRACY

We as citizens of the United States observe politics from afar and the vast majority of us may participate in the political process only to the extent that we go to the polls once a year to vote. We may endeavor to follow the news accounts of our nation's politics as they unfold, and of the consequences those political actions yield, but we have little power to influence our "democratically" elected officials. Perhaps we write an occasional letter to our senator or representative, but we almost inevitably receive a vague and impersonal response explaining why they will vote in our opposition.

Over the decades, our representative democracy has been systematically undermined and has ultimately failed in preserving the well being of the people of this nation. The system that the founding fathers painstakingly devised in order to best serve the interests and the will of the people has been corrupted and the systems of checks and balances on power that they instituted have been stripped away. Most of us accept this reality as being beyond our control and continue to observe, comment, and complain without aspiring to achieving any real change, without any hope of instituting a new system of governance that would instead take directly into account your views, and the views of your neighbors, and would empower you to make real positive change possible in your communities.

This site will attempt to explore in depth the places in the world where people are successfully bringing about that type of change in the face of similar odds, where an alternate form of democracy, which is called participatory or direct democracy, is taking root. Initiative, referendum & recall, community councils, and grassroots organizing are but a few ways in which direct/participatory democracy is achieving great success around the world.

Our system of representative democracy does not admit the voice of the people into congressional halls, the high courts, or the oval office where our rights and our liberties are being sold out from underneath us. Our local leaders and activists in our communities, and even those local elected officials who may have the best of intentions are for the most part powerless to make real positive change happen in our neighborhoods, towns and villages when there is so much corruption from above.

In places like Venezuela, Argentina, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Ecuador, Brazil, South Africa, India, and the Phillipines, new experiments in grass roots community based governance are taking place. There is much to be learned from these and other examples of participatory democracy from around the world when we try to examine how this grass-roots based governance could begin to take root here in our own country in order to alter our political system so that it might better serve the American people.

In the hope that one day we can become a nation working together as a united people practicing true democracy as true equals, we open this forum…

Over the decades, our representative democracy has been systematically undermined and has ultimately failed in preserving the well being of the people of this nation. The system that the founding fathers painstakingly devised in order to best serve the interests and the will of the people has been corrupted and the systems of checks and balances on power that they instituted have been stripped away. Most of us accept this reality as being beyond our control and continue to observe, comment, and complain without aspiring to achieving any real change, without any hope of instituting a new system of governance that would instead take directly into account your views, and the views of your neighbors, and would empower you to make real positive change possible in your communities.

This site will attempt to explore in depth the places in the world where people are successfully bringing about that type of change in the face of similar odds, where an alternate form of democracy, which is called participatory or direct democracy, is taking root. Initiative, referendum & recall, community councils, and grassroots organizing are but a few ways in which direct/participatory democracy is achieving great success around the world.

Our system of representative democracy does not admit the voice of the people into congressional halls, the high courts, or the oval office where our rights and our liberties are being sold out from underneath us. Our local leaders and activists in our communities, and even those local elected officials who may have the best of intentions are for the most part powerless to make real positive change happen in our neighborhoods, towns and villages when there is so much corruption from above.

In places like Venezuela, Argentina, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Ecuador, Brazil, South Africa, India, and the Phillipines, new experiments in grass roots community based governance are taking place. There is much to be learned from these and other examples of participatory democracy from around the world when we try to examine how this grass-roots based governance could begin to take root here in our own country in order to alter our political system so that it might better serve the American people.

In the hope that one day we can become a nation working together as a united people practicing true democracy as true equals, we open this forum…

LATEST ENTRIES:

Tuesday, February 26, 2008

Action Network: BBC Adventures in e-Democracy

Posted by

Democracy By The People

at

8:53 AM

![]()

Labels: BBC Action Network, e-democracy, EUROPE, Participatory Democracy, UNITED KINGDOM

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment